We simultaneously crave and fear the famous (or infamous?) abstract games. However, for some reason, we feel it's important for our kids to play such games. The good news is that there is a solution. Not just one, but many.

Are we not smart enough?

I don't even know what I've heard more from parents:

"I'm not smart enough for chess..."

"It would be nice if they played chess, but it's too complicated for my kids..."

"Somehow, games like chess don't seem exciting enough for my kids; nothing really happens in them."

Let's start by acknowledging that chess is not the only option. There are plenty of simple, home-friendly, easily manageable short games. And each of these has a big brother. So, there's no need to jump straight into the most complex ones; we can experiment with our and our children's limits in simpler, shorter, and therefore less risky forms.

Progress doesn't require us to strain ourselves; it comes naturally. As development unfolds, games can become more intricate, and we can accompany the boys for as long as possible. And let's not be afraid if they outgrow us; that's actually what we want, isn't it?

No time? No money?

Yes, that's a problem too. Buying something expensive and challenging just to not have time for it afterward? Ideally, kids play a lot both at school and at home, and it's crucial for parents to be part of the play at home.

Of course, it's great if a child attends a chess club, but the quality leisure time spent at home with parents, where play is an important organizer, cannot be replaced. Fortunately, not only long and complicated games are smart. If we have a few simple tools on hand, we can quickly put together games at home that are easy to learn and play.

Why are abstract games considered boring?

No, it's not because they lack color. Rather, it's because we don't encounter them at the right time and in the right context—not the first time, not the second time, and not the umpteenth time.

I've taught Kalah to more than 300 people, the rules of International Checkers to at least 200, and I can't recall a single adult or child who resisted. Instead, I often hear that they not only learned the game but also bought it and continue to play. Both games are regularly present in my educational sessions as well.

Imagine the joy of attending the graduation party of a disadvantaged family and seeing one of your students pull out a Kalah to play a few rounds. Achieving this isn't magic; the games themselves do the work. It's a matter of conscious building—what, when, and in what order?

Why do we have time for development?

At times, impatience arises even among educators and parents. We want everything immediately because another child might already know it, our child could know it too, or according to the curriculum, we shouldn't be at this point anymore.

Meanwhile, children are walking their own path, and we can help them gently and modestly, but there's no need to stress if there's no significant issue. And it's certainly not a big problem if someone at the age of 5-6 is not competing with chess players with an Elo rating of over 2000.

Learning is a journey, part of which includes finding rhythm or motivation, and various games can superbly assist with that. Playing with many games is easiest when they are quick to learn and short. A parent or educator can filter from a two-minute game whether the children enjoyed it, whether it's worth delving into, and whether we've found the beginning of a path.

We've gathered a few pairs of games, trios of games for you, where you can transition from simple and light fun to more thoughtful game structures. Let's take a look at these!

Tic-Tac-Toe and Line-Winning Games

Many games are underrated worldwide, and Tic-Tac-Toe is certainly one of them. With an average rating of 2.7 on the BoardGameGeek list, it doesn't make it into the top 25,000 games. Although Gomoku only has a 5.9 rating, its difficulty is 1.85 compared to Tic-Tac-Toe's 1.28, and the playing time has increased from 1 minute to 5 minutes. And this is what we are looking for.

Tic-Tac-Toe is a wonderful game for preschoolers because the playing field is limited, and the number of pieces is finite, making it easy to grasp. The goal is to have three of our pieces next to each other diagonally, vertically, or horizontally. The two players take turns, and someone quickly wins – if we understand the game, that someone will be the starting player.

Gomoku's board is larger, and more pieces need to be placed next to each other. Moreover, we can let it go, playing on a square grid, drawing circles and crosses with a pencil. I have many exciting memories of playing under the desk from school.

And you can twist things even further. Tőtikék (this is a Hungarian term, indicating that the rows need to be filled) are line-winning games where the placed stones/pieces slide towards the arrow until they hit an obstacle (the edge of the board or another stone/piece). So, often, you can only place them where you want after lengthy constructions, but meanwhile, the situation is constantly changing.

So, with our children, we can sit down to play Tic-Tac-Toe even in preschool, and we can also make a cute, personalized set. From here, it will be very easy to move on to more complex line-winning games, comfortably following the path of development.

2x5 or 10x10

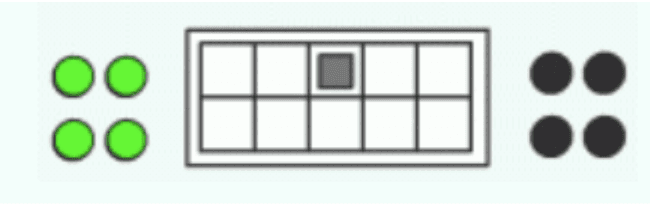

Many may not know, but in a slight exaggeration, you can play checkers on any size board. Lahti is the simplest form I know. There are 2 rows with 5 fields each, and one of the two middle fields is marked, for example, with a crown. Alternately, we place our 4 pieces each, and the battle can begin. The winner is the one who knocks out all the opponent's pieces or the one who has only 1 piece left but can enter the field marked with the crown.

Moves can be made laterally and diagonally, hitting is mandatory if possible, which we can execute by jumping over the opponent's piece if there is an empty space behind it. The game goes quickly; you can play 8-10 rounds in under 20 minutes while learning the basics of checkers.

Most people play checkers on an 8x8 board, but International Checkers on a 10x10 board and its rules fulfill the potential in checkers. With 20 pieces each, the goal is to annihilate the opponent. We can only move forward, diagonally, on dark squares, and only one at a time. If we can jump over the opponent, we must do it, and thus, we hit the piece.

If there are multiple hits on the board, we must always choose the longer one because there are combo hits, as often seen in movies. Moreover, hitting backward is also possible and obligatory. If you reach the opponent's baseline, your piece becomes a king (double-height figure), which can then move any number of spaces and hit from any distance.

Checkers is fundamentally an exciting, aggressive game that channels and releases aggression within its boundaries. The rules are simple, but on larger boards, there is plenty of depth. You can even venture into competition, but, as we know, it's not the primary goal.

A Friendly Encounter with Sets

When we look at a pile of something, it's good to have a rough idea of how much it is because many conclusions can be drawn from it. For example, whether a handful of change is enough for a cookie to go with the soda. In many board games, we estimate quantities, and a basic game for this is Nim, which has numerous variations.

Typically, the goal is for you to pick up the last pebble, which, according to some rule, are in sets during the game, and generally, you can only pick from one set in your turn. For a while, we just pick up pebbles, then we start counting, and then we leave that behind too because at a glance, we know whether the set has an even or odd number of elements, and that's enough for us.

After many Nim rounds, Mancala won't be unfamiliar. Here, too, we work with quantities, as, aside from our own holders, taking one by one counterclockwise, we scatter our pebbles. The goal is to have more pebbles in our collector by the end of the game than the opponent's. Recognizing quantities is important because with strategic moves, we can either steal or make multiple moves, thus collecting more pebbles.

It's evident that we're not at the Nim level anymore, but perhaps it's also clear that the path might be easier from there than if we started directly here because Mancala can be 20 minutes of aimless dropping if we're not ready for it.

Recognizing quantities and patterns play a significant role even in the deepest game in the world, Go. On the massive board of Go, seeing the strength of patterns, understanding the possibilities within them is essential for successful gameplay. And so, we progress from a handful of neatly arranged pebbles to Go, which has been conquering for more than 4000 years.

Let's Keep an Eye on Variations!

I won't go into further details, but I'd like to draw attention to variations in two more popular games.

Nine Men's Morris is also a well-known and once-played game that can become dull after a while. But did you know that there are various Nine Men's Morris boards? Is the experience the same on each? The answer is definitely no. Similar but not identical, and this is crucial, especially if we have children who are reluctant to step out of their comfort zone, but we still want them to encounter new things.

At the beginning of the text, chess was extensively discussed, probably the most well-known game globally and rightfully popular, yet understandably feared. In my experience, for children not particularly interested in chess, the events tend to unfold too slowly. There are many exciting variations of chess as well.

In our book 'Jól játszani' (Playing Well) co-authored with József Jesztl, we introduced a Kobold Chess, which, on a smaller board, incorporating elements of Shogi, offers a more dynamic, faster alternative for those interested in chess but not committed enough to the traditional slow pace.

Courage, Serenity

Let's not abandon the world of abstract games just because they may seem a bit challenging. Instead, let's seek simpler starting points and build meticulously; it's worth it. It's surely not a coincidence that these games have been with us for hundreds, sometimes even thousands of years, while in the realm of modern board games, titles that are merely 10-20 years old often already feel worn out.

Let's unravel their secret together, and the first and most crucial step, one that justifies their existence, is to play them!

No spam, ever. Unsubscribe anytime.

Spread the Fun of Learning!

Love our content? Show your support by sharing our page with your friends and help us inspire more families and educators with the joy of learning through play! Your shares truly make a difference. Thank you for being a wonderful part of our community!