The most common situation I've encountered countless times is when a parent asks for a board game recommendation for a child who struggles with losing. And the typical response? Cooperative games.

Why? So they don't experience failure—or at least, so they don't lose alone.

To me, this is simply avoiding the real issue. I firmly believe that children (and late-blooming adults) can learn valuable lessons about winning and losing through board games.

And while we're on the subject, I think the importance of winning is often overlooked. In my experience, many people don't know how to handle victory either. Some struggle to acknowledge their own good performance, while others overreact or become dismissive toward others.

So, there's plenty of work to be done here, too—not just when someone withdraws or becomes aggressive after losing. Of course, the latter is more noticeable, which is why we often see it as a bigger problem.

Of course, it's understandable that we don't always want to take the harder path. But how can we expect real solutions if we simply eliminate challenging situations?

To me, it seems like we're just postponing the issue rather than addressing it.

I've managed to foster board gaming cultures in several different environments, where the value of playing together goes beyond the win-loss dynamic.

We love playing, we enjoy being together, and it doesn't really matter who wins—this, in simple terms, is the goal.

I believe that those who instinctively recommend cooperative games as the perfect solution—despite their best intentions—are actually being counterproductive.

Why is it a bad thing if a child breaks down in front of us Whether as a parent or a teacher, this is exactly the kind of situation we should welcome—because it means we can see that something is wrong. Would it be better if they only lost control after class, out on the street, or just with their friends instead of with us? We wouldn't have the chance to help. Board gaming is constant simulation, repeated practice, and compared to real-life struggles, it's a low-stakes environment. I think that's amazing—so let's be willing to face difficult moments from time to time and allow things to move in the right direction.

The Pedagogical Perspective

Despite all this, the main reason I dislike the automatic recommendation of cooperative games is that, from a pedagogical perspective, board gaming itself is already a cooperative activity—even when playing a competitive game.

In fact, many times it seems that cooperative learning situations are even better achieved through competitive games.

Let's take a closer look at what I mean!

I start from the premise that the most popular and widely played cooperative board games are often cooperative simply because they are dualistic.

To put it simply: the players are the "good guys," and the game itself is the "bad guy."

The natural consequence of this structure is that these games can often be played solo. Think of Pandemic, the Forbidden series, or well-known children's games like Max or Orchard.

In these games, all information is open, meaning that at any given moment, the best possible move can be determined—and as long as one person in the group knows it, the whole team can follow along.

A common issue with these games is the emergence of an alpha player, who dominates decision-making and takes control of the group.

And why is this a problem from a cooperative standpoint?

Let's take a look at Spencer Kagan's principles of cooperative learning.

Pandemic

The game is perfect for high school students as it offers intellectual stimulation, fosters teamwork, and educates players about global health and geography facts.

Players take on different roles as scientists, researchers, and medical experts, working together to treat infections, prevent outbreaks, and find cures before time runs out. Using action points each turn, they travel, treat diseases, share knowledge, and collect cards to discover cures. The team wins if they find all four cures before too many outbreaks occur or time runs out.

Tools

1 game board, 7 role cards with matching pawns, 59 player cards, 48 infection cards, 96 disease cubes (in 4 colors), 6 research stations, 4 cure markers, 1 outbreak marker, 1 infection rate marker, and a rulebook.

Skills Developed

The game enhances cooperative strategy, critical thinking, teamwork, decision-making, and crisis management, as players must work together to stop the global spread of diseases.

1. We rely on each other: everyone's performance affects the achievement of the goal.

Now, let's think about a game of Pandemic. What is the goal? Managing the outbreak. Technically, everyone's moves contribute to success. But is this truly the case?

Can I even make a bad move? Only if no one notices that it's a bad move. This might happen in a group of completely inexperienced players. However, what's far more common is that others correct me or confirm my choice if I was already thinking correctly.

So, in reality, we are mostly dependent on at least one person understanding the game well.

But let's broaden the perspective and reconsider the true purpose of the game session—and as a parent and educator, this feels like a much more meaningful approach.

In this case, the goal is not just preventing the outbreak, but rather spending quality time together and enjoying the experience.

But if I'm bored because someone always tells me the right answer, or I feel guilty because we lose due to my mistakes, or I end up dominating the group as the alpha player, then none of these feel like a truly cooperative experience to me.

Here are some collections of cooperative board games, including some of the latest releases!

2. Individual responsibility.

This is closely connected to the first point. If my actions directly impact the team's performance, then my responsibility is significant.

But in typical, popular cooperative games, this doesn't really exist—for the reasons already mentioned. The situation actually resembles poor group work, where the top-performing student does all the problem-solving for the rest.

In cooperative games where some information is hidden from the rest of the group, this principle works much better.

But—it also works in almost every competitive game.

I believe my responsibility is enormous in a card game, if I consider the goal to be having a high-quality game session. I need to make good, smart decisions, or I won't provide enough of a challenge for my opponents, and they will get bored.

No one can help me because they don't know my cards, and it's not in their interest to assist me.

I am on my own, yet my responsibility affects everyone at the table.

This is beautiful cooperation—even while competing.

No spam, ever. Unsubscribe anytime.

Spread the Fun of Learning!

Love our content? Show your support by sharing our page with your friends and help us inspire more families and educators with the joy of learning through play! Your shares truly make a difference. Thank you for being a wonderful part of our community!

3. Simultaneous interactions.

From this perspective, I don't see a major difference between cooperative and competitive board games.

- In a cooperative game, we think together, analyze options, and make joint decisions.

- In a competitive game, I observe my opponents, anticipate their moves, and adjust my strategy accordingly.

In a well-designed board game, there will always be simultaneous interactions, keeping everyone engaged and active.

And then there are real-time party games with fast-paced simultaneous actions (e.g., Jungle Speed, Dobble), where competition is at its peak—yet in a way, we still exist in a cooperative setting because of the shared, interactive experience.

4. Equal participation.

Well, yes. I've seen far more bored players in cooperative games, simply because others constantly tell them what to do.

In Hanabi, for example, I do have personal responsibility—I need to memorize information that others can't remember for me.

Yet, even in Hanabi sessions, I've often seen players who spent the entire game just discarding cards and occasionally stating the information suggested by their teammates.

They mechanically followed along, but they weren't truly engaged.

In these cases, equal participation is clearly compromised.

Hanabi

A clever cooperative deduction card game with a unique twist.

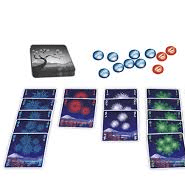

Players hold their cards facing outward, meaning they can see everyone else's cards but not their own. Using limited clue tokens, they must help each other deduce which cards to play in the correct order to complete a perfect firework display. Playing incorrect cards loses fuse tokens, and if all are lost, the game ends in failure. The team wins by completing as many firework sequences as possible before running out of moves.

Tools

60 cards (five colors, numbered 1-5), clue tokens, and fuse tokens

Skills Developed

Enhances logical thinking, memory, communication skills, and teamwork.

When we sit down to play a board game, we collectively agree to have a good time, follow the rules, and try to perform at our best. This doesn't always happen, but that's the goal.

This is how everyone can participate equally, and how individual responsibility becomes real.

We rely on each other—because if I play poorly, cheat, or quit mid-game, I ruin the experience for the entire group.

The interactions are constant—even when it's not my turn, I'm watching, calculating, planning, because otherwise, I won't be able to play well enough.

Many popular cooperative games fail to create this dynamic due to their solitaire-like nature, whereas competitive games, thanks to hidden information and uncertainty, naturally do.

I find this fascinating—but let's circle back to the beginning.

We shouldn't play cooperative games just to avoid winners and losers. We should play them because the game itself is good.

If we enjoy collaboration, then let's seek out good cooperative games.

But cooperative games are far from the miracle solution many believe them to be.

Board gaming itself is already a cooperative experience—let's make the most of it!