I recently found myself in a very interesting environment: I was invited to join a community discussion on play (Stereo Akt). I can’t fully capture the workshop itself, but fortunately, I wrote down my introductory remarks, so I can share those. Afterward, we played, discussed the concept of play, and then processed our experiences through a collaborative creation. It was awesome.

"My name is Máté Lencse, I’m a teacher and game designer, and I focus a lot on the educational benefits of board games. However, my topic for today may not fall clearly into that category, even though it likely belongs there.

Two years ago, together with József Jesztl, we published a playful book titled Manóváros, whose quasi-slogan is that “play surrounds us; in reality, anything can be played with, so anything can become a board game.” The book only includes game boards and rules, while the materials needed must be collected from nature: sticks, pebbles, sunlight—something different for each game. This book was individually shrink-wrapped and shipped from China, via Russia and Belarus, by train. By that point, I had already given up on seeing it as a professional task to keep up with the latest releases. I was quite bothered by the board game industry, by the consumerism emerging within it, and this shrink-wrapping and shipping pushed yet another button for me. Does the message of the book mean anything if its production, transportation, and distribution leave such a large ecological footprint?

There are so many things to play with—we can be extraordinarily creative in how we approach play. Can this ever-present playfulness somehow influence the very genre of board games?

If you come play with me, we’ll look at and try some alternative things together. We’ll play with money, color as a form of play, arrange pebbles, and talk about dice and playing cards. I’ll show you a game of mine available for borrowing and also Manóváros. And, of course, we’ll talk.

Here are three comments, stories, questions to consider first.

I’m not a hypocrite; I partly live off the market myself, searching for alternative paths. But in the meantime, my games are being released, because this is what I know how to do—ideas keep coming. For me, this situation is a bit like what I experience in my other job: as a civilian, I perform tasks that should be the responsibility of the state. But if I don’t, kids are left behind on the roadside. If I do, the state continues to ignore them. If I don’t release games, it won’t reduce the oversupply, but if I do, I contribute to it. Either way, it’s hard to speak credibly about how this isn’t entirely okay.

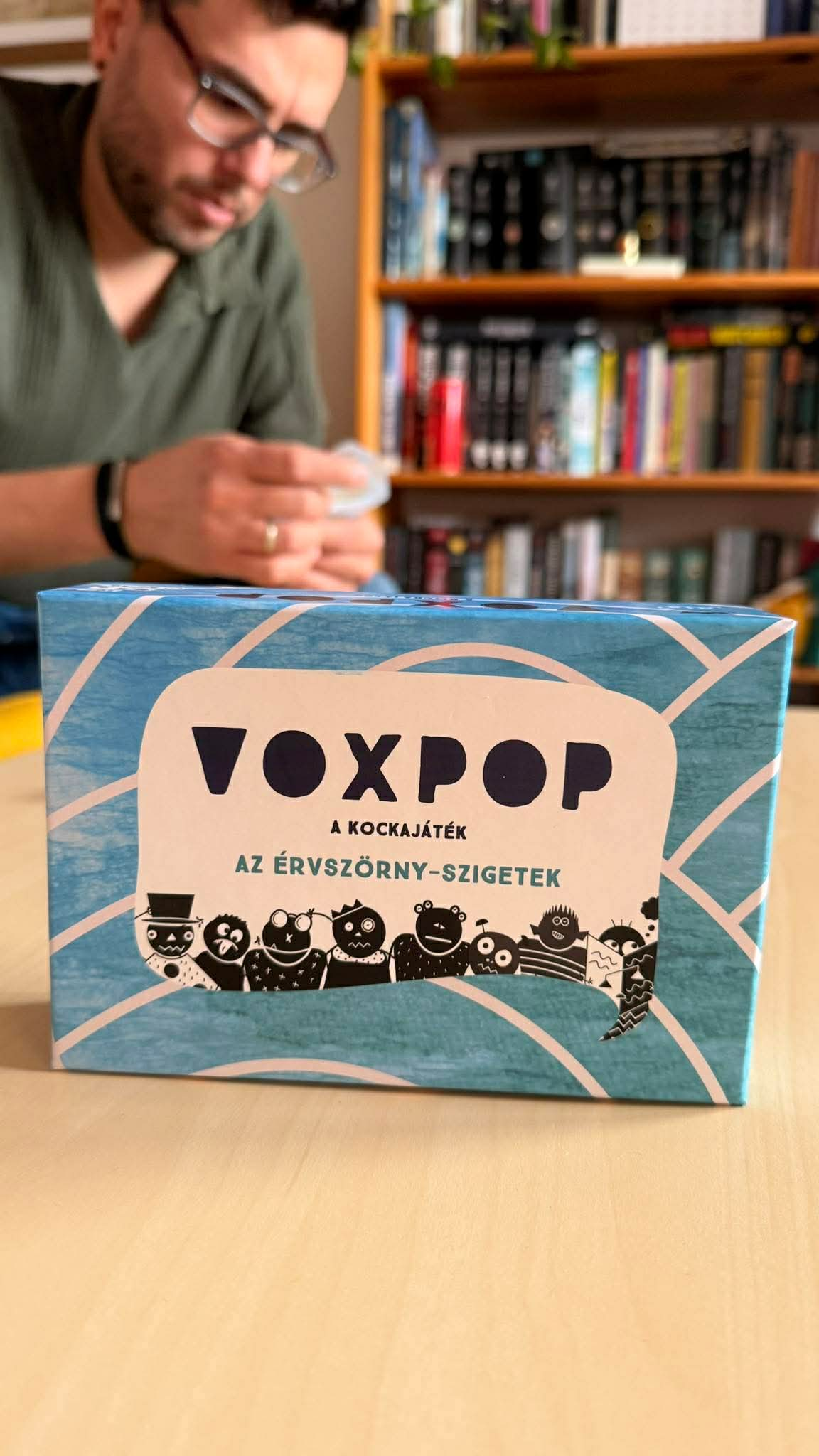

I launched a game-lending project that wasn’t a failure, but not a success either. Some of my ideas I didn’t publish, only making a few copies that can be borrowed from me. I brought the most popular one here—I’ll tell you more about it later—but for now, I’ll just say that several people wanted to buy it. “This is amazing; I need this on my shelf.” NEED! (Which, of course, is entirely against the purpose for which I created it.)

And what does this have to do with pedagogy? With education? Sometimes wandering onto atypical paths is pedagogy itself. It can have a powerful impact on attitudes if I give a child a playful experience drawn from their own environment, from everyday activities. I’ve already been swallowed up, chewed, and spat out by consumer society. There isn’t much order in my immediate surroundings, but I have a few ideas that might survive, and later, with someone else, perhaps even make an impact."