Yesterday, I gave a lecture at a conference titled Board Game Pedagogy – Focusing on Atypical Games. I only had 60 minutes, so I couldn’t set overly ambitious goals; instead, I wanted to give a sense of what board game pedagogy is about. To do this, we played a round of Happy Salmon and then thoroughly broke it down from a pedagogical and professional perspective to see everything such a simple game can actually develop.

After that, I briefly summarized the core principles of board game pedagogy. I’m currently working on refining them—updating what we wrote in our 2018 book with the insights and experiences of the past few years. Here’s where I am now:

A game is a game. We start it, we play it, we finish it—and we patiently expect the impact to come from that process.

We don’t teach tactics or strategy; instead, we learn how to learn. Making mistakes, experimenting, exploring possible paths freely and without stakes are all essential parts of the learning process.

Making pedagogical goals explicit, overemphasizing them, or creating overtly educational situations is not recommended, because it breaks the authenticity of the play experience, which in turn harms motivation.

In the ideal play situation, every participant is truly present: voluntarily, motivated, and giving their best.

The practitioner of board game pedagogy—be it a parent, teacher, or anyone else—is a participant in the play situation, not a game master.

We do not use educational or “awareness-raising” board games. What we seek is a genuinely good play experience, and to achieve this—while keeping pedagogical goals in mind—we choose board games from the existing game market.

The task lies in providing a selection of board games, offering recommendations, and motivating players—always with respect for individual choice and autonomy. In practice, this means ensuring a variety of options from which players can choose based on their interests, mood, and knowledge.

Both classic abstract games and modern board games are part of the repertoire. By incorporating modern games, board game pedagogy maximizes its potential impact, while at the same time valuing knowledge of historical foundations and showing the evolution of games.

Board game pedagogy does not aim to immerse deeply in a single game; rather, it seeks to present a wide variety of games and mechanisms, which requires broad knowledge of the board game landscape.

Board game pedagogy can be applied anywhere.

I divided the 30 participants across four tables, each receiving a package of atypical games. I’m still only experimenting with the topic, so the definition is fluid, but I would describe them as games that haven’t been taken all the way through the winding road of product development. They are puritan games, with minimal components, often using everyday objects, and frequently without any theme.

We started with Nim games, using pebbles, and then looked at what meaningful play can emerge from just a single die: Pig.

We also took a short detour to explore publishing solutions that carry simplicity and restraint in creative ways. The best example of this is Chris Handy’s Pack O Game series, but we also examined a few titles from Oink Games.

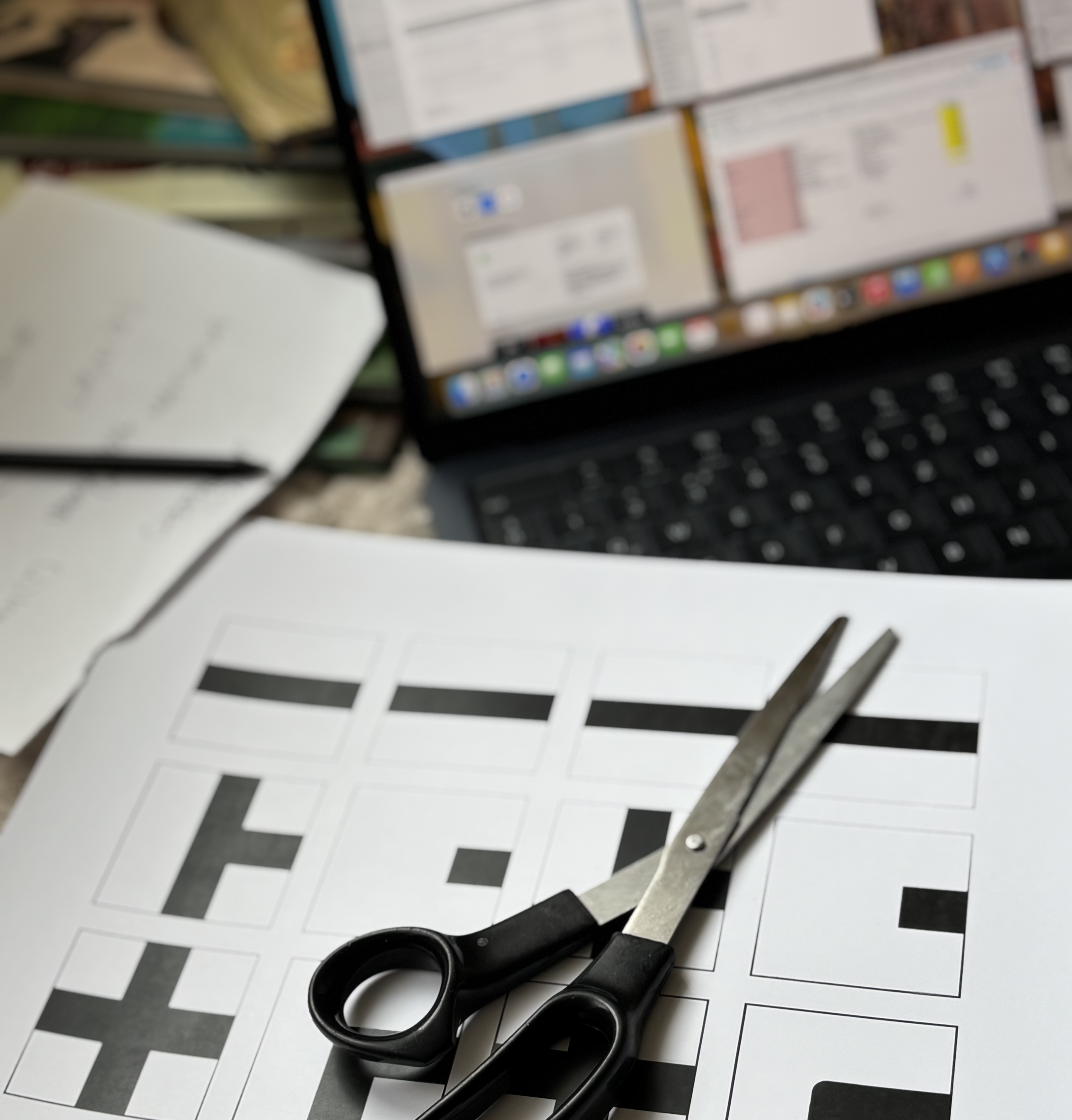

After that, we focused on print & play microgames. We began with a money-based game—Coin Age—then I introduced our bookmark game, Mark & Play, and finally, we did some coloring. Following in the footsteps of the great Sid Sackson and his masterpiece Games of Art, participants could try the Flame Duel from our own Coloring Book.

At the end, we explored questions such as: What pedagogical value might children gain from being exposed to such games? Can these kinds of games provide a full play experience? Or am I misinterpreting product development—perhaps it’s not profit-driven but instead aimed at optimizing play experience? Can we lower our material expectations, for the planet’s sake, while still satisfying our passion for games? And can a game designer make a living if they release their work for free?

There were more questions than answers, but one kindergarten teacher remarked that the idea of “playing anytime, anywhere, with anything” still beautifully characterizes preschoolers. We know exactly whom we can learn from—if we believe there is learning to be done.