Introductory Thoughts

The development of modern board games—if not immediately, then inevitably—also brought with it new ways of thinking about their pedagogical value. Every year, thousands of new games are released, and many of the most important and popular titles are available in Hungarian as well. If we focus on the positive side, this results in an enormous variety.

Many different games mean many different ways of thinking. We can experience a wide range of activities, explore countless themes, play alone or in large groups, play for three or four minutes or even three or four hours, and play with toddlers as well as with elderly players.

Whatever we are looking for, we will find it. For example, if we are looking for board games that effectively develop different competencies, the selection is vast. What is needed is the right attitude and a solid knowledge of games—after that, our only task is to teach the game and let it do its work.

Emotional Awareness

It is no coincidence that emotions come up so often when we talk about board games. We frequently focus on whether someone can handle losing, or how they deal with success. Almost any board game can serve as an example here, as games provide a safe environment in which we can experience emotions while striving for symbolic goals—and learn how to manage them.

The now commonly used expression poker face also comes to mind: non-verbal communication is often key to success in games, just as emotional regulation is essential for clear thinking in more challenging situations.

As parents and educators, one of our most important goals is to allow children to develop through joyful play, freely experiencing their emotions while respecting one another. Board gaming as an activity can support the development of this area exceptionally well.

Creativity

Isn’t a board game too regulated a medium to support creativity? Let’s take a look at how some excellent games manage to encourage creative thinking within clearly defined boundaries.

Dixit (2008) is a true modern classic that has long escaped the confines of the game box and is widely used as a training tool and even in formal education—for introductions, expressing emotions and moods, and more. Beautiful, unique illustrations offer dozens of associations, supported by clever and simple rules. What do I see in an image? What do I say about it? Who thinks similarly, and who differently? How can I communicate clearly without being too obvious? All of this happens within a light, entertaining family game.

We might also think of Concept (2013) or Imagine (2016). Both are based on solving simple challenges, but in Concept players communicate using pictograms, while in Imagine they create meaningful images from transparent cards. If this isn’t out-of-the-box thinking, what is?

Problem-Solving

At first, we might think of games that present explicit logical challenges. The most obvious example is the Rubik’s Cube (1974), but the world of solo logic games also fits here well—an early major success was Rush Hour (1996), where players must cleverly slide pieces to free a small plastic car from increasingly difficult puzzles.

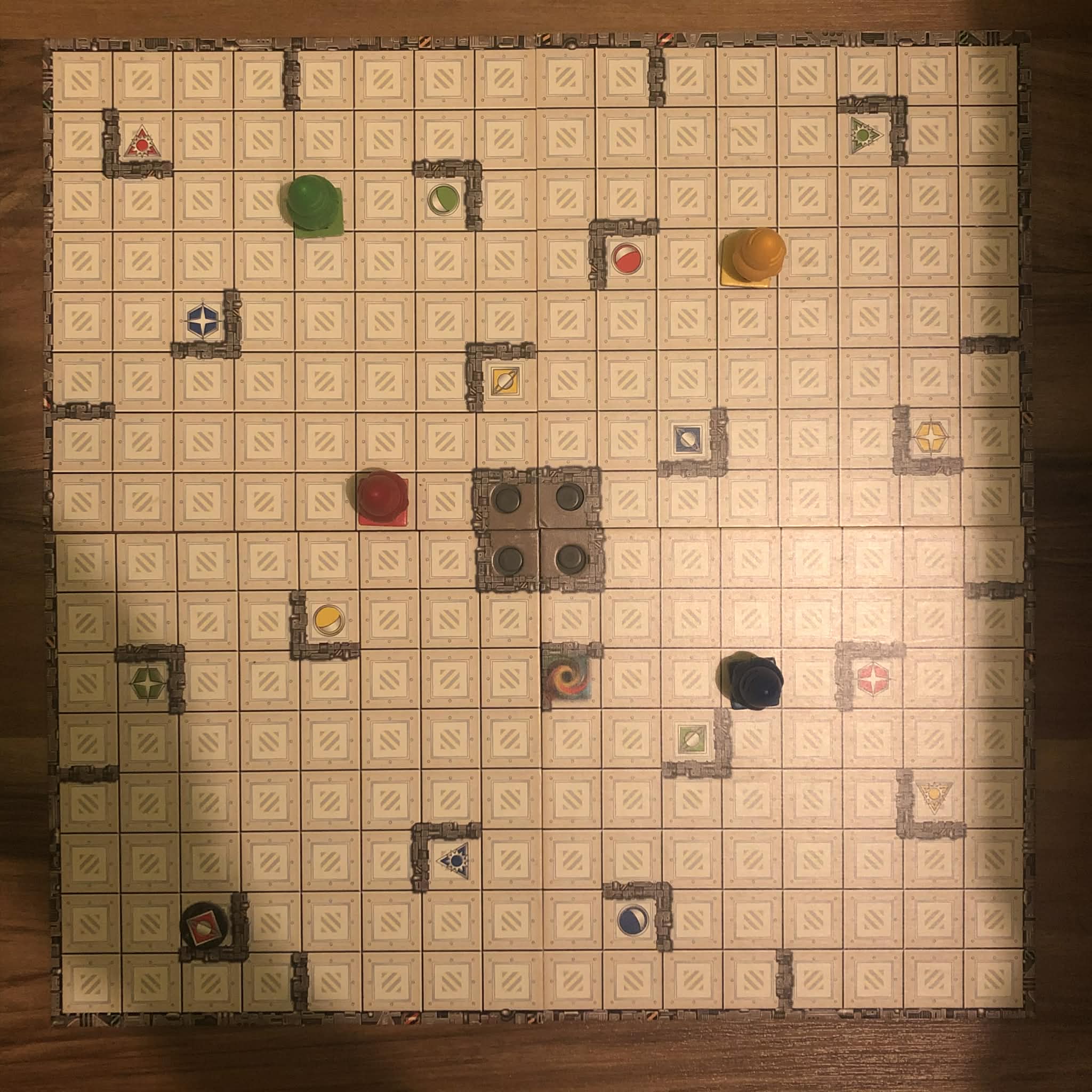

A personal favorite of mine is Ricochet Robots (1999), where players mentally program the movement of different robots to reach a target as quickly and efficiently as possible. Another interesting trend in modern board games is the popularity of Tetris-like elements, used in a wide range of engaging gameplay systems. The common thread is always the same: covering a given area with specific elements under specific rules as efficiently as possible—for example Ubongo (2003) or the more complex Bärenpark (2017).

Critical Thinking

If we start from the idea that all good board games are built around interpreting available information in order to make the best possible decisions, then we are on solid ground—no matter what we play with children. This can be cooperative, like Pandemic (2008), or competitive, like Codenames (2015).

Strong game literacy is important so we can recommend games of varying difficulty levels—from very simple decision-based games to complex systems that support development through depth and challenge. Reaching games like Tzolk’in: The Mayan Calendar (2012), where correct interpretation of numerous variables over long periods is required, is not an easy journey.

Resilience

Here again, cooperative games come to mind—such as Forbidden Desert (2013)—where players can process difficult situations together, supporting one another if things go wrong or even if the entire game is lost. Not only can we observe supportive behavior as a model, but we can actively provide it.

This is why, within board-game-based pedagogy, we recommend that educators participate in the game whenever possible. Through their behavior patterns and reactions to situations, they can teach and model an enormous amount.

Flexibility

Adaptation and re-planning are fundamental aspects of board gaming. Information constantly changes, and carefully designed plans often collapse. Moreover, most board games are not games of perfect information, so players must adapt to ongoing uncertainty.

This applies to simple card games like Love Letter (2012) or No Thanks! (2004), as well as to complex systems like Agricola (2007). Games create situations in which we can safely try ourselves in challenging contexts that require flexibility—without real-world stakes.

Curiosity

This area can once again be approached from the activity of board gaming itself. Playing many different games, exploring various mechanisms and themes, places us in a wide range of situations. Seeking new challenges and dealing with them reveals our relationship to curiosity—and our potential for growth.

If I had to name a specific game, I would mention the 2020 hit MicroMacro: Crime City, where constant searching, understanding, and solving crimes is at the core, supported by a huge and visually captivating map.

Empathy

We haven’t yet touched on the world of educational and awareness-raising board games—now seems like the right time. In Hungary, Szociopoly (Social Monopoly, 2010) is undoubtedly a pioneering title, showing how difficult it is to survive on social benefits and occasional work. Another strong example is Mentortársas (Mentor Board Game, 2013), which illustrates the nearly impossible situation of disadvantaged students in public education.

I myself also designed a game for the Heroes’ Square Foundation titled Holnap hősei (Heroes of Tomorrow), focusing on the importance of paying attention to others and offering help whenever and wherever possible.

That said, this broader perspective may not even be necessary. As the examples above already show, even “regular” board games require a high level of mutual attention if we truly want to play well. Board gaming is, in itself, a social activity that becomes far less safe and enjoyable without empathy. What is comfortable for whom? What game do we choose? Where do we sit? Can we eat? Establishing a shared gaming culture is essential in groups of children, and empathy is a key element of that.

Valuing People and Nature

The relationship between humans and nature is a prominent theme in board games. Some defining titles of recent years include Photosynthesis (2017), Wingspan (2019), and Cascadia (2021). There is no shortage of thematic material to draw from.

At the same time, we cannot ignore the relatively large ecological footprint of board gaming: plastic production, packaging waste, manufacturing leftovers, and long shipping routes. This is why it is worth discussing alternative approaches with children—game libraries, homemade games, and print-and-play, downloadable and printable games.

Connectedness

When The Mind (2018) appeared, there was even debate about whether it was a board game at all. Its success and impact, however, are undeniable, and symbolically it fits perfectly here. It is a card game in which players cannot speak or signal in any way, yet must collectively play their cards in ascending order. Impossible? And yet it became a light, successful, and universally understandable game.

Board gaming is about connection: choosing a game together, following the rules together, enjoying ourselves together. In this sense, the Hungarian word “social game” expresses this idea beautifully—perhaps even more so than the English term board game. Cooperative games amplify this effect further, as demonstrated by Bomb Busters (2024), the most recent Spiel des Jahres winner.

Closing Thoughts

Using board games for pedagogical purposes is a motivation-based approach. We offer students an enjoyable activity through which they can develop—almost unnoticed and with joy—in areas that we, as professionals, consider important. One of the core principles of board-game-based pedagogy is to let games remain games. We should not turn play into an overtly educational situation; instead, we should allow children to engage in the most natural activity for them, voluntarily and driven by intrinsic motivation

The short reflections above are merely invitations and starting points—attitudinal guides that suggest first steps. From there, everything can be adapted in practice by educators and learners alike.