The Argument Monster Islands

The VoxPop product line is expanding with a new game: we’ve completed the sibling of the card game, a dice game. Since this turned out to be one of the most interesting development processes I’ve been part of so far, I thought it might be worth giving it a longer introduction.

The other path is when I develop a game on commission, typically for a specific brand. These usually don’t end up in commercial distribution, and the client’s requirements play a very strong role — the theme often influences the game balance itself. I’ve written a bit more about this elsewhere. Of course, the boundaries are often blurred, and that was the case this time as well — but something else happened here too.

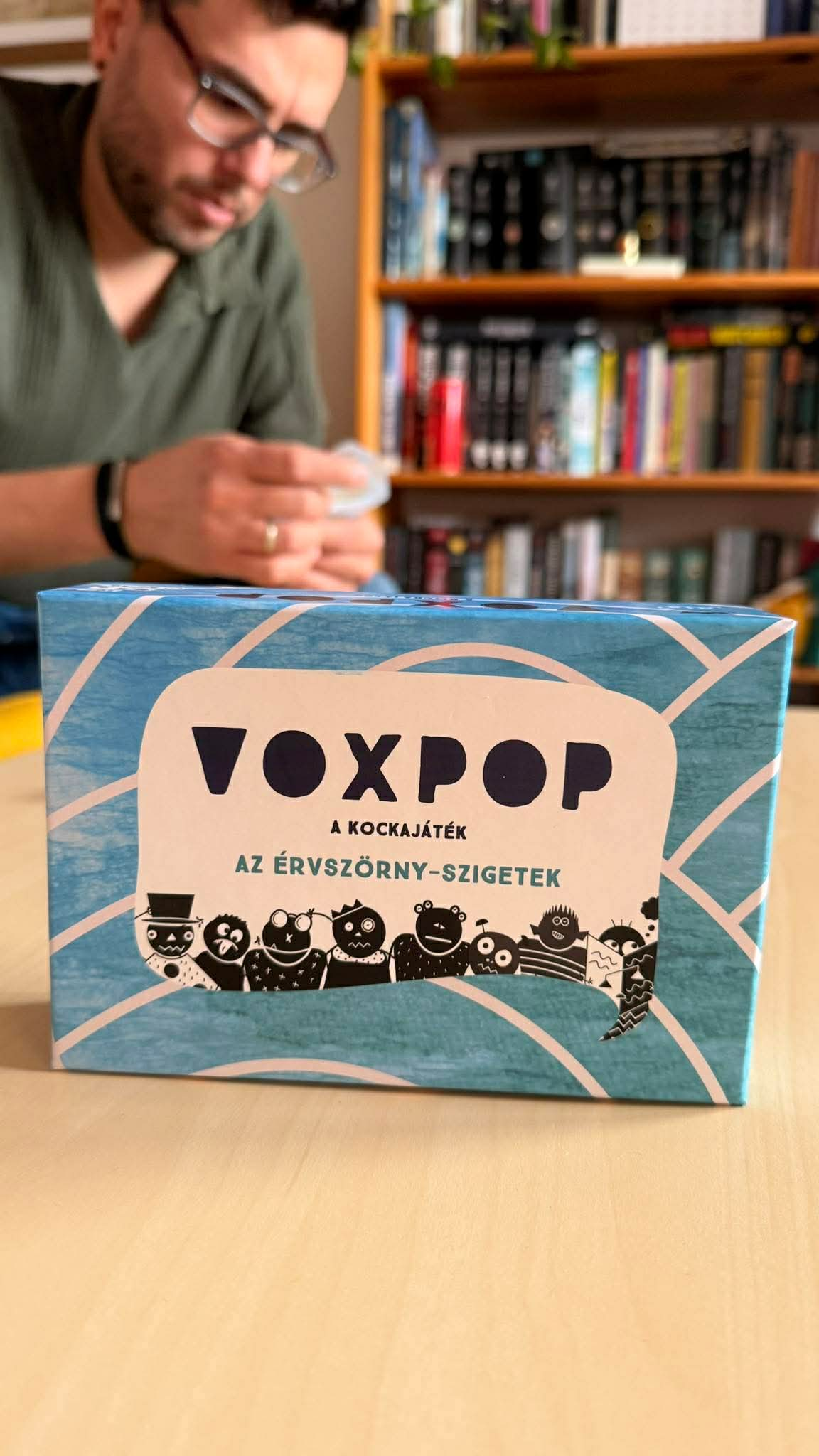

VoxPop – The Card Game was released in 2022 and was well received by its audience. By now, only a handful of copies remain. Because of this, the Demokratikus Ifjúságért Alapítvány (Foundation for Democratic Youth) decided in 2024 that there should be some kind of continuation. They included it in a grant application, secured funding for it, we were able to develop it in 2025, and by 2026 it was released.

The start was scheduled for the summer of 2024, at a debate camp where members of the national debate club network come together. All I knew was that this would be the place to lay the foundations. I had one basic idea: if there was already a card game, then there should also be a dice game — but I didn’t want to go any deeper than that.

We had the opportunity to survey all the camp participants about what they thought of the existing games: what they liked about them and what they felt was missing. The process was coordinated by the two of us together with Panna Kovács-Makó, who was responsible for the game’s illustrations and graphic work.

Of course, you can’t design a game together with an entire camp full of children and young people, but the foundations fell into place, and we formed a small design team from among the participants. Here, we first explored dice game mechanics using a range of different board games (Calavera, Deep Sea Adventure, Age of War, Corinth, Noch mal!, Paku Paku).

So we had the feedback, we knew the mechanics, and we knew that developing debate culture was our broader theme. Since there was a clear expectation from the community that the result should feel more like a proper board game, we started thinking in that direction. It was incredibly inspiring to watch everyone throwing in ideas, shuffling cards and dice around, and brainstorming together. And something did come together.

I went upstairs to put my one-year-old daughters to bed, and typed out the first version of the rulebook on my phone.

The next step was creating the first prototype. This was where illustration ideas and graphic directions already started to appear, production questions came up, and — most importantly — the idea could finally be tested in a tangible form. It wasn’t perfect, of course, but we felt it was good enough to present at the end of the camp, and overall we could be satisfied with the process. The camp ended, and the team dispersed.

As a more experienced game designer, it was obviously my responsibility to bring our creation into shape. The first goal was to get the idea into a form that could be properly tested. Here again, we didn’t want to rush ahead or exclude the debate club community, so we started testing in a fairly beta state. I made a rules explanation video and a printable game set — since testing was taken on in different parts of the country. We also created an online questionnaire to collect structured feedback. In parallel with sending everything out, we started testing the game ourselves as well.

Somewhere toward the end of autumn, things finally began to come together, and we could move on to illustrations and organizing production. I won’t bore you with that part — the game is finished, it’s great and it’s beautiful. And if you don’t believe me, go check it out.